The Foundations of Research Design: Ontology, Epistemology, and Methodology

When we begin a research project, it usually starts with a spark—a question we can’t stop thinking about, an injustice we want to name, or a community whose stories deserve to be heard. These big ideas are often what pull us into qualitative research in the first place.

Yet as we move from inspiration to design, we quickly discover that passion alone isn’t enough. To transform a question into a coherent study, we need to engage with some of the philosophical building blocks of research: Ontology, Epistemology, and Methodology.

These three concepts are more than just academic jargon. They shape the very foundation of a project, influencing the kinds of questions we ask, the methods we use, and the claims we make about what we’ve found. If they feel intimidating, that’s understandable—they are abstract, often explained in ways that seem detached from practice. But they don’t need to be overwhelming. In fact, once you see how ontology, epistemology, and methodology fit together, you’ll start to recognize them as essential guides that can strengthen your work and give you confidence in your research decisions.

Foundations: Reality, Knowledge, and Inquiry

Ontology: What is reality?

Ontology is, at its core, a question about being. It asks: What is the nature of reality?

Is there one objective reality that exists independently of people’s perceptions? Or are there multiple realities, shaped by lived experience, culture, and context?

For example, if you believe there is a single truth about a social issue, your research may seek to uncover that truth, leaning toward methods that aim for objectivity. If, on the other hand, you believe there are many truths—different ways of experiencing and interpreting the same event—you might design your research to highlight and honor those diverse perspectives. In qualitative inquiry, we often assume the latter, working from the belief that reality is socially constructed and best understood by listening closely to participants’ lived experiences.

Epistemology: How Do We Know What We Know?

If ontology is about what exists, epistemology is about how we come to know it. Do we believe that knowledge is discovered, waiting to be uncovered like a fossil in the ground? Or do we believe that knowledge is created—constructed through relationships, language, and context?

In practice, this matters because it shapes your stance as a researcher. A positivist epistemology assumes the researcher can remain separate and neutral, uncovering knowledge objectively. A constructivist or interpretivist epistemology, by contrast, acknowledges that researchers and participants co-create knowledge through interaction. This shift has significant implications: it means your voice, perspective, and positionality are not separate from the research but are part of the process.

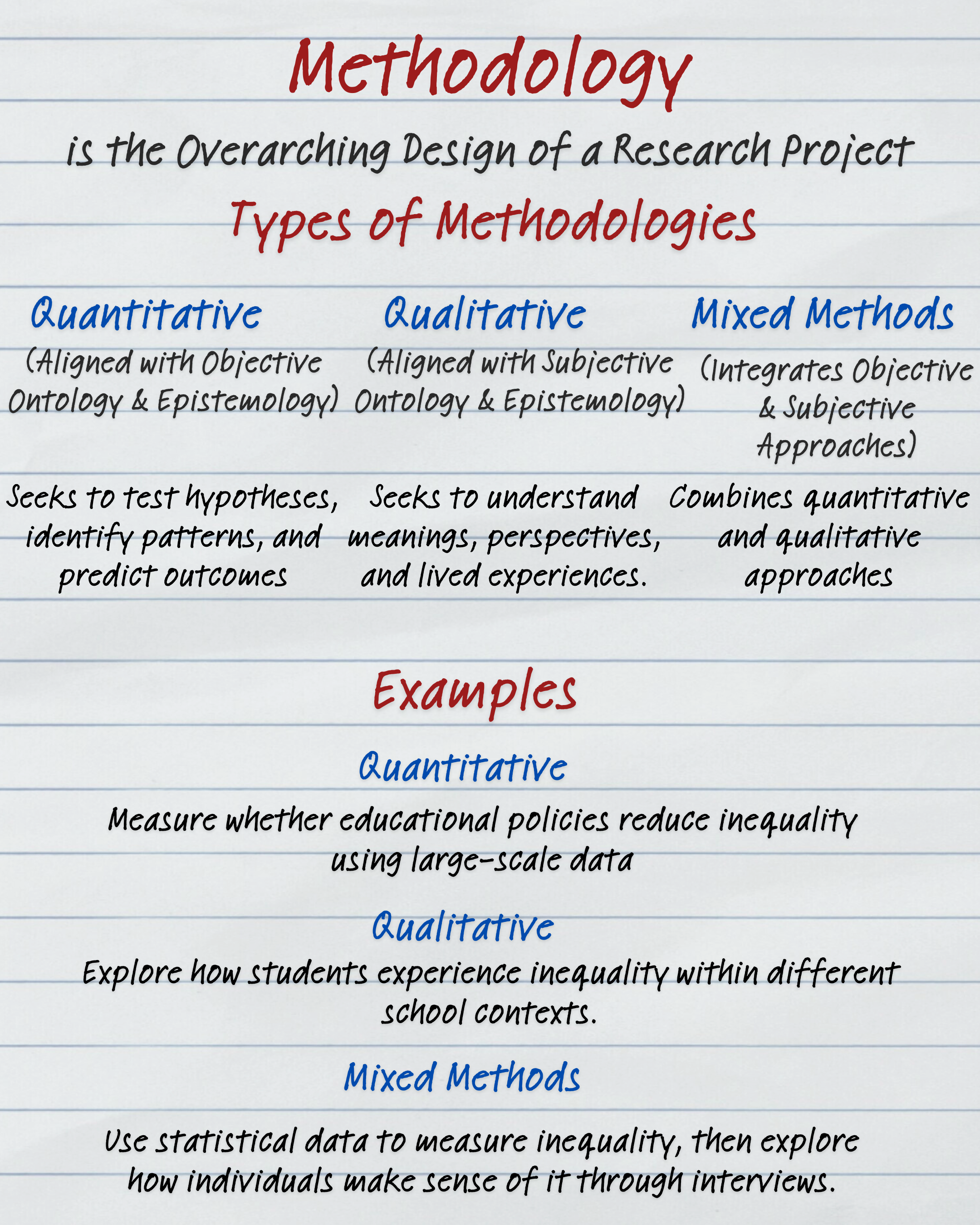

Methodology: How Do We Study Reality and Knowledge?

Methodology is the bridge between your philosophical assumptions and the actual tools you use. It asks:

Given my beliefs about reality and knowledge, what research strategies make sense?

For example, if your ontology posits that multiple realities exist and your epistemology holds that knowledge is co-created, then methodologies such as ethnography, narrative inquiry, or participatory action research may align well. These approaches allow you to enter into participants’ worlds, co-construct meaning, and highlight diverse perspectives. If instead you lean toward a single reality and objective knowledge, you might choose methodologies that emphasize consistency, replicability, and measurement.

Why Does Alignment Matter?

Where students often stumble is when these pieces don’t align. Imagine proposing a study that assumes knowledge is co-created but then describing your role as a “neutral observer.” Or designing a project to explore multiple perspectives, but using a method that assumes only one truth can be uncovered. These mismatches can make a dissertation committee question the coherence of your design—not because your idea isn’t valuable, but because your philosophical foundation and methodological choices don’t line up.

When ontology, epistemology, and methodology are aligned, your research gains coherence and depth. You can explain not only what you did, but why you did it that way. This doesn’t just satisfy academic requirements—it also strengthens your confidence. You begin to see that your choices are not random or merely procedural; they are grounded in a thoughtful understanding of how you see the world and how you believe knowledge is produced.

Moving From Theory to Practice

So, how do you actually use these concepts in your dissertation? Here are a few practical steps:

Write down your assumptions. Start by asking yourself: What do I believe about reality? How do I think knowledge is created? You may be surprised by how much clarity emerges from this exercise.

Check for alignment. Once you’ve named your assumptions, look at your proposed methodology.

Do they match? If you say you believe in multiple realities but describe your study as uncovering “the truth,” you may need to revise your language or approach.

Integrate reflexivity. Recognize that your own identity, positionality, and worldview shape your answers to these questions. Reflexivity isn’t an add-on—it’s part of rigorous qualitative research.

Articulate it clearly. When writing your methodology chapter, don’t just describe your methods; instead, take time to explain your ontological and epistemological stance. This shows your committee (and later, your readers) that your project is well-grounded.

Moving From Ideas to a Solid Research Design

At the heart of it, engaging with ontology, epistemology, and methodology is about moving from inspiration to coherence. It’s about ensuring that the big ideas that drew you to research are translated into a design that is philosophically sound, methodologically rigorous, and authentically yours.

As qualitative researchers, we know that reality is messy, identities are layered, and truths are plural. By reflecting on these foundations, we don’t reduce complexity—we honor it. We recognize that every study is shaped by assumptions, and by making those assumptions explicit, we create research that is not only stronger but also more transparent, ethical, and meaningful.

So as you design your dissertation, don’t shy away from these big words.

Ask yourself:

What do I believe about reality? How do I think knowledge is created? And what approaches will best reflect those beliefs?

The answers to those questions may evolve, but the act of wrestling with them will always move your research from big ideas toward better, more grounded scholarship.

If you find yourself wrestling with these ideas or are unsure how to translate them into your own research design, you’re not alone — let’s connect and work through them together. I’d be glad to help you turn your ideas into a clear, grounded, and confident research design — one that reflects your perspective, aligns with your goals, and strengthens the story your study is meant to tell.